JohnHB

is one Smokin' Farker

- Joined

- Dec 15, 2012

- Location

- Sydney NSW

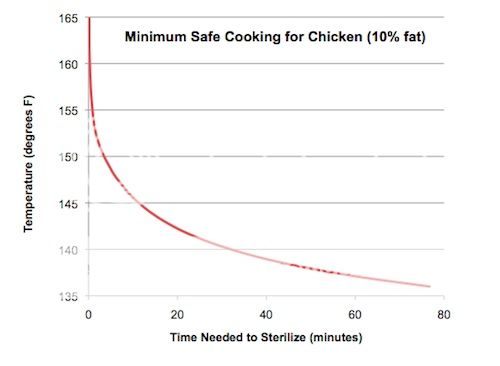

It seem that the many brethren hold a misconception that chicken to be safe must be cooked to a minimum of 165F. At 165F chicken is almost pasteurised instantly and is therefore considered safe. Consider this if you cook your chicken for 150F for about three minutes it is pasteurised to the same except as cooking it to 165F. This is demonstrated in chart shown here under. Obviously It is much more moist cooked to 150F versus 165F. But hey why listen to me I am a chartered accountant that likes to cook. So I have copied an article from a much learned source below. So stop the bull dust about food safety if you do not understand the science!

John

SERIOUS EATS

Sous-Vide 101: Low-Temperature Chicken

Posted by J. Kenji López-Alt, April 14, 2010

About the author: J. Kenji Lopez-Alt is the Chief Creative Officer of Serious Eats where he likes to explore the science of home cooking in his weekly column The Food Lab. You can follow him at @thefoodlab on Twitter, or at The Food Lab on Facebook.

Sous-Vide Chicken Breast

There is a misconception about food safety, and particularly as it applies to low-temperature water bath cooking (often inaccurately referred to as "sous-vide" cooking*). The thought process goes something like this:

*Sous-vide refers only to the vacuum-packing aspect, which, while it often goes hand in hand with low-temp water baths, it is not the defining characteristic of the cooking technique.

Point 1: Industry-standard food safety instructions refer to the range between 40°F and 140°F as the bacterial "danger zone," and recommend not allowing any foods to sit within that range for any longer than four hours.

Point 2: Low-temperature cooking often takes place in temperature ranges within this "danger zone." For example, cooking a steak for several hours at 130°F.

Conclusion: Low-temperature cooking is unsafe.

It seems reasonable to make such an assumption, but it ignores one important factor: industry standards for food safety are designed to be simple to understand at the expense of accuracy. The rules are set up such that anybody from a turn-and-burner at Applebee's to the fry-dunker at McDonald's can grasp them, ensuring safety across the board.

But for single-celled organisms, bacteria are surprisingly complex, and despite what any ServSafe chart might have you believe, they refuse to be categorized into a step function. A number of factors, including saltiness, sweetness, moisture, and fat content can affect growth, not to mention the effects of temperature are much more subtle.

For instance, take a look at the graph below. The data was taken directly from the USDA's guide to obtaining a 7.0 log10 relative reduction in salmonella in chicken. For those of you who don't know what a 7.0 log10 relative reduction is, it's the bacterial equivalent of sticking a stick of dynamite in an anthill. The vast majority of the baddies become harmless, dead, ex-baddies.

Essentially, the red line in this graph indicates how long a piece of chicken needs to be cooked at a specific temperature in order to be deemed safe for consumption. So, for example, we see that at 165°F, the chicken is safe pretty much instantaneously (hence the 165°F minimum internal temperature recommendation by the USDA—they are being very conservative and assuming you will bite into it the second it reaches that temp). Whereas at 140°F, the chicken needs to be held for 35 minutes to be safe.

Now with a conventional oven, this chart is totally useless. Since your cooking environment is much higher than your desired final temperature there is no way to hold your meat at a steady low temperature—it hits 140°F, then continues to go up and up and up. So the best you can do is take the center to 165°F to ensure that the entire piece of chicken is safe to consume, by which point it's already expelled a great deal of its moisture.

Low-temperature cooking changes all of that. With a temperature-controlled water bath, you have the ability to not only cook chicken to lower temperatures, but more importantly, to hold it there until it's completely safe to consume.

What does this mean for a home cook? It means that you no longer have to put up with dry, 165°F chicken.

Chicken cooked to 140°F, like the one in the photo above, is just as safe as chicken cooked to 165°F, and incomparably moister and more tender. It glistens with moisture as you cut it. It practically oozes juices into your mouth as you chew. Bad image, I know (sounds like the food writer's version of chewing with your mouth open), but it's the only way I can explain how much better chicken is this way.

Of course, straight out of the bag, the chicken has not reached temperatures high enough to precipitate the Maillard reaction, so you'll still need to finish it off on the stovetop. I cooked the chicken above on the skin-side in canola oil, though butter works well too.

And as for skin and bone being on or off, I prefer to keep the skin on just because I love crispy skin, and browning chicken without skin will always leave you with a stringy layer, no matter what you do. Skin lets you brown without sacrificing texture.

I found little difference between chicken cooked bone-in vs. bone-off. With traditional cooking methods, the bone helps insulate meat from the high cooking temperatures. Not a problem with a water oven. Feel free to go boneless if you so desire.

Cooking at even lower temperatures is safe and possible, however at a certain point, the meat starts to take on an off-putting jelly-like texture. For me, 140°F has all the moisture I want without losing the feel of pan-roasted chicken.

Finally, the last drawback with cooking chicken in a water bath is that you develop very little fond—the flavorful browned bits that stick to your pan when you sear meat. The bad news is that this makes forming a pan sauce impossible. The good news is that the reason those flavorful bits aren't on the pan is because they are still right in the chicken where they belong. A sauce made from a separate stock or a vinaigrette-style dressing do my chicken just fine.

While the recipe that follows is easiest with a controlled water bath, feel free to use my cheap and easy cooler hack to do it ghetto-style.

Continue here for Sous-Vide Chicken with Sun-Dried Tomato Vinaigrette »

Printed from http://www.seriouseats.com/2010/04/sous-vide-basics-low-temperature-chicken.html

© Serious Eats

John

SERIOUS EATS

Sous-Vide 101: Low-Temperature Chicken

Posted by J. Kenji López-Alt, April 14, 2010

About the author: J. Kenji Lopez-Alt is the Chief Creative Officer of Serious Eats where he likes to explore the science of home cooking in his weekly column The Food Lab. You can follow him at @thefoodlab on Twitter, or at The Food Lab on Facebook.

Sous-Vide Chicken Breast

There is a misconception about food safety, and particularly as it applies to low-temperature water bath cooking (often inaccurately referred to as "sous-vide" cooking*). The thought process goes something like this:

*Sous-vide refers only to the vacuum-packing aspect, which, while it often goes hand in hand with low-temp water baths, it is not the defining characteristic of the cooking technique.

Point 1: Industry-standard food safety instructions refer to the range between 40°F and 140°F as the bacterial "danger zone," and recommend not allowing any foods to sit within that range for any longer than four hours.

Point 2: Low-temperature cooking often takes place in temperature ranges within this "danger zone." For example, cooking a steak for several hours at 130°F.

Conclusion: Low-temperature cooking is unsafe.

It seems reasonable to make such an assumption, but it ignores one important factor: industry standards for food safety are designed to be simple to understand at the expense of accuracy. The rules are set up such that anybody from a turn-and-burner at Applebee's to the fry-dunker at McDonald's can grasp them, ensuring safety across the board.

But for single-celled organisms, bacteria are surprisingly complex, and despite what any ServSafe chart might have you believe, they refuse to be categorized into a step function. A number of factors, including saltiness, sweetness, moisture, and fat content can affect growth, not to mention the effects of temperature are much more subtle.

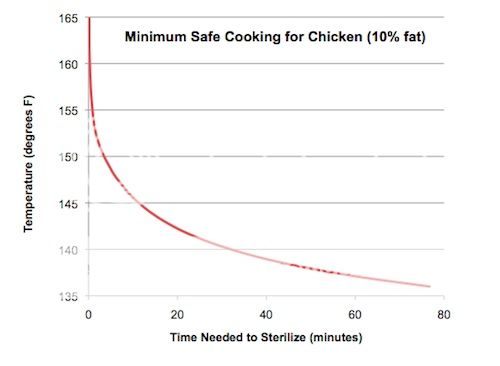

For instance, take a look at the graph below. The data was taken directly from the USDA's guide to obtaining a 7.0 log10 relative reduction in salmonella in chicken. For those of you who don't know what a 7.0 log10 relative reduction is, it's the bacterial equivalent of sticking a stick of dynamite in an anthill. The vast majority of the baddies become harmless, dead, ex-baddies.

Essentially, the red line in this graph indicates how long a piece of chicken needs to be cooked at a specific temperature in order to be deemed safe for consumption. So, for example, we see that at 165°F, the chicken is safe pretty much instantaneously (hence the 165°F minimum internal temperature recommendation by the USDA—they are being very conservative and assuming you will bite into it the second it reaches that temp). Whereas at 140°F, the chicken needs to be held for 35 minutes to be safe.

Now with a conventional oven, this chart is totally useless. Since your cooking environment is much higher than your desired final temperature there is no way to hold your meat at a steady low temperature—it hits 140°F, then continues to go up and up and up. So the best you can do is take the center to 165°F to ensure that the entire piece of chicken is safe to consume, by which point it's already expelled a great deal of its moisture.

Low-temperature cooking changes all of that. With a temperature-controlled water bath, you have the ability to not only cook chicken to lower temperatures, but more importantly, to hold it there until it's completely safe to consume.

What does this mean for a home cook? It means that you no longer have to put up with dry, 165°F chicken.

Chicken cooked to 140°F, like the one in the photo above, is just as safe as chicken cooked to 165°F, and incomparably moister and more tender. It glistens with moisture as you cut it. It practically oozes juices into your mouth as you chew. Bad image, I know (sounds like the food writer's version of chewing with your mouth open), but it's the only way I can explain how much better chicken is this way.

Of course, straight out of the bag, the chicken has not reached temperatures high enough to precipitate the Maillard reaction, so you'll still need to finish it off on the stovetop. I cooked the chicken above on the skin-side in canola oil, though butter works well too.

And as for skin and bone being on or off, I prefer to keep the skin on just because I love crispy skin, and browning chicken without skin will always leave you with a stringy layer, no matter what you do. Skin lets you brown without sacrificing texture.

I found little difference between chicken cooked bone-in vs. bone-off. With traditional cooking methods, the bone helps insulate meat from the high cooking temperatures. Not a problem with a water oven. Feel free to go boneless if you so desire.

Cooking at even lower temperatures is safe and possible, however at a certain point, the meat starts to take on an off-putting jelly-like texture. For me, 140°F has all the moisture I want without losing the feel of pan-roasted chicken.

Finally, the last drawback with cooking chicken in a water bath is that you develop very little fond—the flavorful browned bits that stick to your pan when you sear meat. The bad news is that this makes forming a pan sauce impossible. The good news is that the reason those flavorful bits aren't on the pan is because they are still right in the chicken where they belong. A sauce made from a separate stock or a vinaigrette-style dressing do my chicken just fine.

While the recipe that follows is easiest with a controlled water bath, feel free to use my cheap and easy cooler hack to do it ghetto-style.

Continue here for Sous-Vide Chicken with Sun-Dried Tomato Vinaigrette »

Printed from http://www.seriouseats.com/2010/04/sous-vide-basics-low-temperature-chicken.html

© Serious Eats